How Your Learners *Actually* Learn with AI

What 37.5 million AI chats show us about how learners use AI at the end of 2025 — and what this means for how we design & deliver learning experiences in 2026

Hey Folks!

Over the last year, a lot of progress has been made in how we’re using AI for learning — but we are still preoccupied with the wrong (or perhaps, not the most important) questions. Every week, I see folks debating back and forth about whether learners should be using AI: does using AI constitute cheating? By using AI, are learners becoming “cognitively lazy” and undermining the very purpose of learning?

Meanwhile, learners have moved on. They’re already using AI—routinely, deliberately, and in ways that (if we look at the research on how humans learn) are perhaps surprisingly productive.

Back in June, I reported on a large scale study by OpenAI of how people were using ChatGPT in their day to day lives and work. The study showed two things:

Lots of people are using AI to help with the learning process.

Most people who sought AI’s didn’t just ask Ai to do the learning work for them: they asked for the support they needed get to the answer themselves.

Last week, Microsoft released a similar analysis of a whopping 37.5 million Copilot conversations. These conversation took place on the platform from January to September 2025, providing us with a window into if and how AI use in general — and AI use among learners specifically - has evolved in 2025.

Microsoft’s mass behavioural data gives us a detailed, global glimpse into what learners are actually doing across devices, times of day and contexts. The picture that emerges is pretty clear and largely consistent with what OpenAI’s told us back in the summer:

AI isn’t functioning primarily as an “answers machine”: the majority of us use AI as a tool to personalise and differentiate generic learning experiences and - ultimately - to augment human learning.

Let’s dive in!

What the Study Looked At (& What it Didn’t)

The Copilot report analyses 37.5 million de-identified conversations from consumer users—not enterprise or education accounts. Each interaction gets classified by intent (learning, searching, getting advice, creating), topic domain (maths & logic, science, language learning), device type (desktop vs mobile), and timing (time of day and month).

To be clear: this is not 360 data. Conversations are anonymised: we don’t know who’s a student or teacher. We can’t evaluate learning outcomes or quality. But, what we do get access to instead is equally valuable: behavioural patterns at scale such as:

What % of all AI interactions relate to learning?

When learning interactions spike.

Which devices people prefer to use when learning with AI.

Which domains learners explore most with AI.

How Learners Are Using AI

Looking at the data, four they themes emerge in learner behaviour:

1. Learning with AI is mainstream

Across all Copilot conversations, “Learning” ranks #4 overall for intent. Not a niche use case. Not edge behaviour. When learning consistently appears as a top reason people use a general-purpose AI tool, something fundamental has shifted. Learning with AI is no longer a novelty or workaround—it’s infrastructure.

Learners don’t “decide” to use AI anymore. They assume it’s there, like search, like spellcheck, like calculators. The question has shifted from “should I use this?” to “how do I use this effectively?”

2. Learners are using AI as a tutor, not an answers machine

The persistent myth about AI in education is that learners primarily use it to bypass thinking. The Copilot data tells a different story. Learning interactions cluster around explanations, step-by-step guidance, conceptual clarification, and help working through problems. This aligns almost exactly with what learning science tells us supports understanding—scaffolding, worked examples, and guided practice.

If learners wanted shortcuts, Google already solved that problem years ago. What they’re choosing instead is support while thinking. They’re not asking AI to complete their work; they’re asking it to help them understand how to do it themselves.

3. AI-supported learning happens during deliberate, focused work sessions

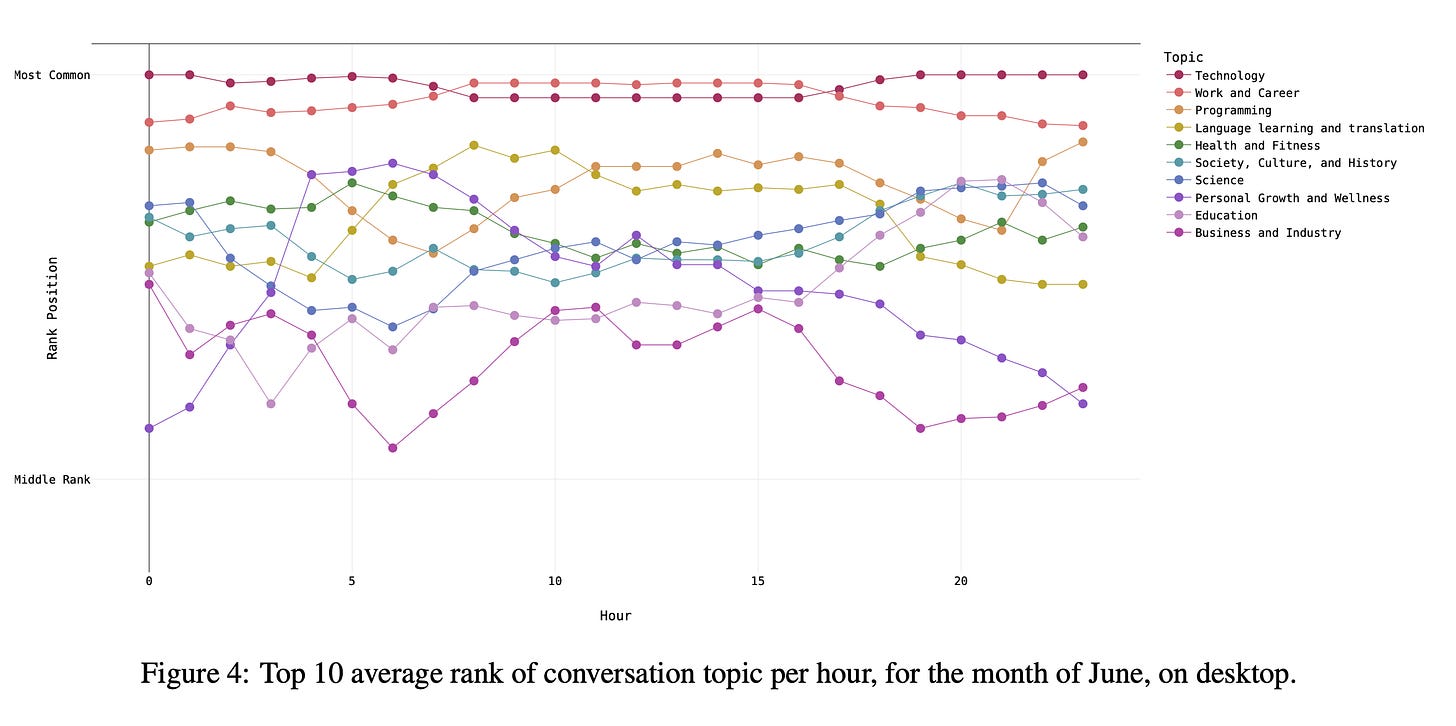

Perhaps the most revealing finding is this: learning with Copilot is overwhelmingly desktop-based and concentrated during work and school hours. This is not casual, on-the-go behaviour. It’s not last-minute mobile cramming and it’s not happening primarily late at night.

Learners turn to AI when they sit down to work and study. They use AI to solve problems, build skills and make sense of difficult material in the flow of learning and work. Put another way, AI is showing up where cognitive effort already exists suggesting that it’s augmenting focus, rather than replacing it.

Learning interactions concentrate heavily in maths & logic, science, and language learning. These are domains characterised by cumulative knowledge, abstraction, and high cognitive load—areas where traditional instruction often struggles to support learners effectively, and where getting stuck can derail progress entirely.

Learners aren’t using AI randomly. They’re using it strategically, precisely where they experience the most friction. This tells us something important: AI is filling real gaps in the learning support infrastructure, not creating artificial demand.

Is The Way that Learners Use AI Changing?

In June 2025, I wrote about learners using AI to redesign the courses we give them. At the time, that argument was based on prompt-level evidence—examples of learners asking AI to quiz them, scaffold tasks, explain concepts at different levels, or support motivation and emotional regulation. What we’re seeing now doesn’t contradict that picture — it confirms it’s operating at scale.

Comparing OPenAI’s data from June with the Microsoft data published last week, we see consistency in the fact that learners still use AI to fix design gaps—missing scaffolding, inaccessible explanations, inadequate practice. In December 2025, learners continue to treat AI as a learning partner (help me to learn X). Much more rarely do they use it as a cheating tool (do X for me).

If the Copilot data tells us anything, its that the behaviours that we saw emerging in June 2025 aren’t occasional or reactive anymore — they’re embedded in regular study routines and they happen during focused, intentional learning sessions.

In June, learners showed us what they wanted from AI. By the second half of 2025, their behaviour shows they’ve stopped waiting for us to provide it—they’ve built their own support systems around the gaps we left.

Implications for Instructional Designers & Educators

This data doesn’t demand any radical reinvention of our day to day work, but it does demand some re-alignment with the realities of how AI is impacting how our learners learn in practice.

Here’s what that this could like in practice:

Stop designing as if AI use is optional

Learners are already integrating AI into their learning workflows. Designing as if they aren’t creates friction, not integrity. The question isn’t whether they’ll use AI—it’s whether our designs acknowledge and work with that reality, or whether we force them to work around us.

Stop treating AI as a “policy issue” that lives in the syllabus.

Start building AI-acknowledged workflow steps into the task: add a required “AI touchpoint” box in the instructions (e.g., Use AI to generate 3 alternative explanations of this concept; pick the best one and justify why it fits the context), plus a short “What I asked / What I changed / What I learned” reflection.

Design for AI-supported cognition

Assume learners will ask AI for explanations, request examples, and seek clarification mid-task. Design activities that require sense-making, reasoning, and transfer—not just output. If a learner can complete your task entirely with AI and learn nothing, that’s a design problem, not a learner problem.

Stop assigning tasks where the main cognitive move is producing a clean output (summary, slide deck, short answer).

Start designing “show-your-thinking” activities which require learners to (1) predict an answer before using AI, (2) use AI for a hint or counterexample, then (3) revise their reasoning and label what changed.

Rethink assessment

If AI functions as an always-available tutor, assessments need to surface thinking processes, decision-making, and application across contexts. Text production alone doesn’t tell us much anymore. What we need to measure is whether learners can think with the support they’ll have in the real world—and whether they can transfer that thinking to new problems.

Stop grading the final product as if it’s a proxy for understanding.

Start assessing the decision trail: add a lightweight rubric row for “prompting strategy + verification,” and require an appendix with (a) one AI-generated suggestion they rejected, (b) why it was wrong/incomplete, and (c) the evidence they used to verify the final approach.

Reposition the educator’s role

AI doesn’t remove the need for instructional design—it makes weak design impossible to hide. When learners can get instant explanations and scaffolding from AI, our value shifts even further toward designing meaningful tasks, diagnosing misconceptions, and creating environments where practice, feedback, and reflection are unavoidable. The tasks we design need to be worth doing even when AI is available. That’s a higher bar than we’re used to—and that’s the point.

Stop spending your limited time re-explaining what learners can get instantly from AI.

Start spending it where AI is weakest: run short “misconception audits” (collect 5–10 anonymised AI-supported attempts, spot the shared failure pattern), then teach that pattern explicitly with a targeted mini-lesson + a practice set designed to trigger and correct it.

Concluding Thoughts

The Microsoft data released last week can’t predict the future of learning with AI, but it helps to confirm where we are right now. At the end of 2025, it appears that learners have already made their choice: they’re using AI to support understanding, manage cognitive load, and persist through difficulty. They’re integrating AI into their study routines during their most focused, deliberate learning time and using it strategically in the subjects where they struggle most.

The most important question isn’t whether learners should use AI — that ship has sailed. The biggest question that we must ask and answer at the end of 2025 is whether we’re designing and delivering learning with this new reality in mind, or still pretending it doesn’t exist.

Happy innovating,

Phil 👋

PS: If you want to get hands-on with AI-powered learning design, supported by me and a cohort of practitioners tackling exactly these questions, apply for a place on my AI & Learning Design Bootcamp.