Defining & Navigating the Jagged Frontier in Instructional Design (October, 2025)

What we know about where AI helps (and where it hinders) Instructional Design, and how to manage it

Hey folks!

This week, I launched a survey with Synthesia to bring us up to speed on how learning professionals are using AI at the close of 2025—what’s working, what’s not, and how it’s genuinely impacting our work. If you’ve not responded to it yet, please take ~7 mins to do so (you might even win a place on my bootcamp!).

As I helped to prepare the survey questions, I realised I needed to understand: what has the research been showing us over the last year or so? What patterns have emerged as AI moved from experimentation to standard practice?

So I dived into the evidence, and here’s what I found.

The Study That Changed Everything

In 2023, Boston Consulting Group partnered with Harvard Business School to conduct what would become a landmark study in understanding AI’s impact on knowledge work (Dell’Acqua et al., 2023). Working with 758 consultants—representing 7% of BCG’s individual contributor workforce—researchers gave participants realistic, complex tasks and measured what happened when they used GPT-4.

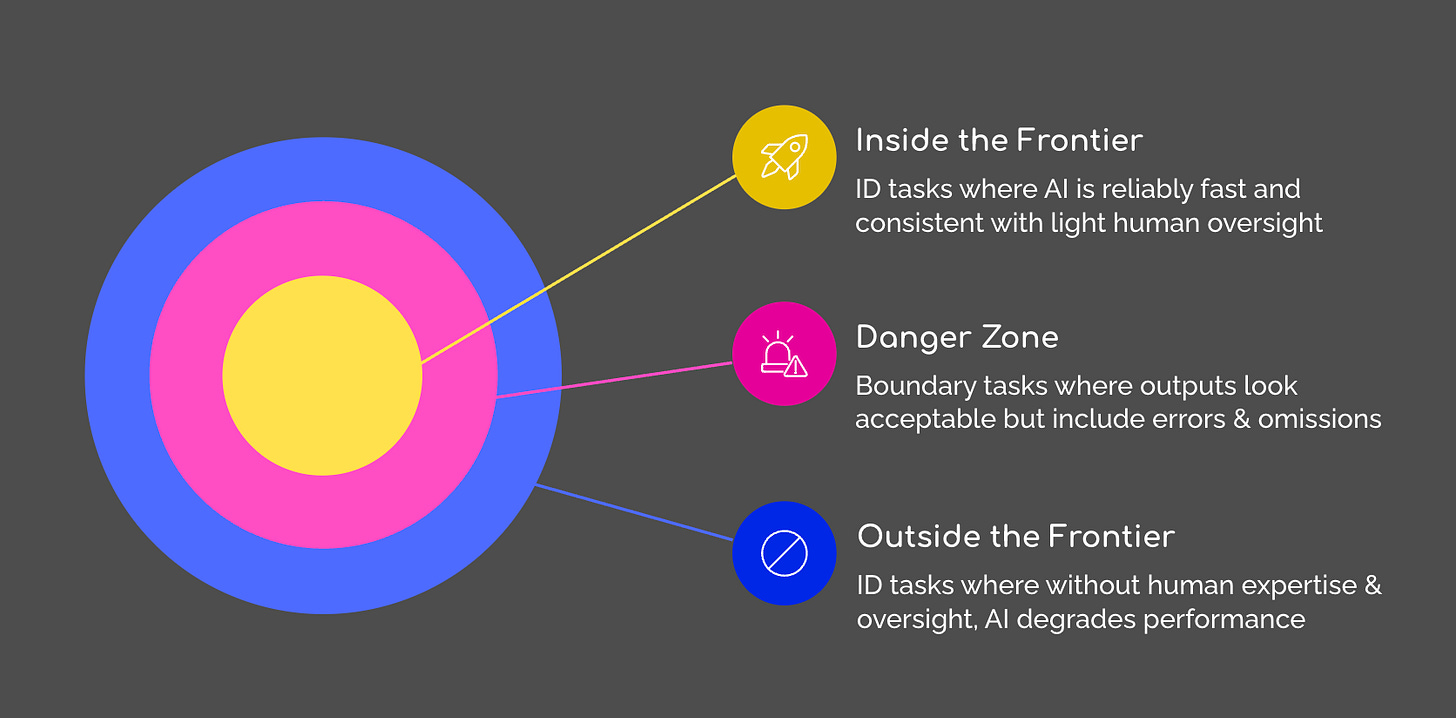

The results revealed something perhaps counterintuitive but critically important: AI doesn’t make people uniformly better or worse at their jobs. Instead, it creates what researchers termed a “jagged technological frontier”—a boundary where some tasks are easily accomplished by AI while others, though seemingly similar in difficulty, lie completely outside its current capabilities (Dell’Acqua et al., 2023).

For tasks inside the frontier, the gains were remarkable. Consultants experienced a 12.2% increase in task completion, worked 25.1% faster, and produced outputs rated 40% higher in quality by human evaluators (Dell’Acqua et al., 2023). These weren’t marginal improvements—they represented genuine transformations in productivity and output quality.

But here’s where it gets alarming: for tasks outside the frontier, consultants using AI performed 19 percentage points worse than those working without it (Dell’Acqua et al., 2023). The AI didn’t just fail to help—it actively degraded performance. Even more concerning, knowledge workers demonstrated what researchers called “mis-calibrated trust,” over-relying on AI precisely where it was weakest and under-using it where it excelled (Hardman, 2025).

The Jagged Frontier in Instructional Design

Two years after the BCG study, we now have comprehensive evidence that this exact pattern is unfolding across instructional design. The 2025 research by Donald H. Taylor and Eglė Vinauskaitė, surveying 606 learning and development practitioners from 53 countries, reveals a watershed moment: for the first time, over 50% of respondents report actively using AI in their daily work (Taylor & Vinauskaitė, 2025). They call this the “Implementation Inflexion”—the point at which AI use becomes standard practice rather than experimental adoption.

But the data reveals something more nuanced than simple adoption statistics. AI use has evolved from “pilot to practice,” marking what researchers describe as crossing an “inflection point” where the conversation has shifted from “if“ to use AI to “how“ to use it well (Taylor & Vinauskaitė, 2025). Teams are now embedding AI into design, delivery, and measurement processes—not just conducting one-off experiments.

TLDR: the data suggests that most practitioners are stumbling across the jagged frontier daily, without understanding the associated risks. Here’s an up to date summary of what we know about the “jagged frontier” of AI use in Instructional Design, shared in the hope that it can help you pull on AI’s benefits while mitigating its risks.

Let’s dive in!

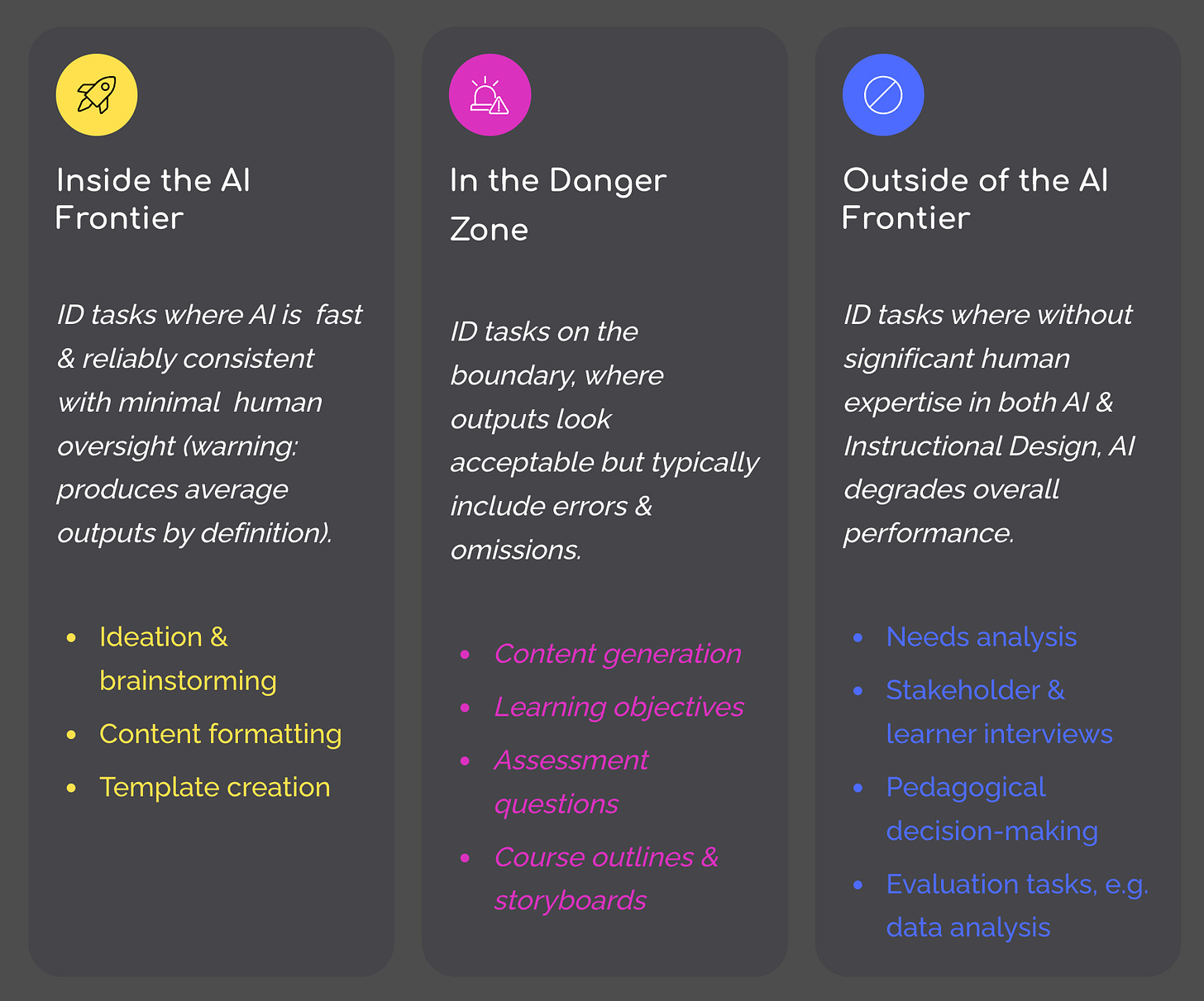

Tasks Inside the Frontier: Where AI Excels

Research across multiple studies has identified specific instructional design tasks where AI consistently delivers value, often with impressive efficiency gains (Choi et al., 2024; McNeill, 2024; Yang & Stefaniak, 2025):

Formatting and structural organisation represent AI’s strongest suit. Creating consistent templates, organising information hierarchically, and developing standardised structures are pattern-driven tasks where AI excels (Ruiz-Rojas et al., 2023). These are genuine time-savers with minimal quality concerns, with research documenting up to 65% reduction in lesson planning time when AI handles structural elements (Hardman, 2025).

Initial ideation and brainstorming benefit significantly from AI assistance. When properly prompted, AI generates diverse options quickly, helping designers overcome creative blocks and accelerate the divergent thinking phase (Harmon & Odom, 2023; Yang & Stefaniak, 2025). Multiple studies confirm that Instructional Designers use AI most frequently for brainstorming and generating initial ideas (Kumar et al., 2024; Luo et al., 2025). Recent research shows a 47% increase in idea diversity during AI-assisted brainstorming sessions and the identification of 40% more design pathway options compared to unassisted brainstorming (Hardman, 2025).

Technical execution tasks like summarisation, basic content structuring, and template generation represent what Ruiz-Rojas and colleagues (2023) describe as AI’s “sweet spot”—where speed and consistency matter more than nuanced judgment. Research documents 95% reduction in MCQ generation time with expert oversight, enabling teams to achieve a 300% increase in assessment volume without sacrificing rigour (Hardman, 2025).

Tasks on the Edge of the Frontier: aka, The Danger Zone

The danger zone is the zone where most performance losses occur in Instructional Design. These tasks sit precariously on the frontier’s edge, sometimes producing acceptable results but often generating generic or pedagogically weak outputs. The danger lies in outputs appearing to be good enough when in reality they are not.

There are four categories or AI use case in the Danger Zone:

Content generation shows wildly variable quality. While AI produces output rapidly, research consistently documents that AI-generated educational content is frequently “formulaic in tone, has shallow emotional resonance, and inconsistent visual detail” (Hardman, 2024). A 2024 study (Winder et al., 2024) examining LLMs for content creation in online learning found that while speed improved, quality concerns required substantial human review and refinement.

Learning objectives exemplify the frontier’s jaggedness. AI can write objectives that look syntactically correct and follow Bloom’s Taxonomy, but they’re often generic or fail to align with actual learning needs (Mollick & Mollick, 2023; Wang et al., 2024). As one researcher notes, “The generated output isn’t always reliable, of course, but it gives me good directions in knowing what’s essential about a topic” (Taylor & Vinauskaitė, 2025)—capturing both the promise and the severe limitation.

Assessment questions can be generated rapidly by AI across diverse question types, but validation for appropriate difficulty levels and alignment with learning objectives remains essential (McNeill, 2024; Ruiz-Rojas et al., 2023). A recent study (Law et al., 2025) found that while ChatGPT could generate multiple-choice questions, they required substantial expert revision due to 6% factual incorrectness, 6% irrelevance, and 14% inappropriate difficulty levels.

Course outlines and structures present an insidious challenge. AI produces comprehensive structures quickly, but they frequently miss critical contextual appropriateness (Kumar et al., 2024). A corporate compliance course and a graduate seminar might receive structurally similar outlines when their pedagogical needs differ dramatically.

Tasks Firmly Outside the Frontier: Where AI Consistently Fails

Certain Instructional Design capabilities still require uniquely human expertise that current AI fundamentally cannot replicate:

Needs analysis demands skills AI lacks entirely. Conducting stakeholder interviews, reading body language, understanding organisational power structures, and identifying political dynamics all require human empathy and interpersonal expertise (Choi et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2024). As Yang and Stefaniak (2025) emphasise, “the human touch—empathy, mentorship, and moral guidance—remains irreplaceable” in education.

Strategic pedagogical reasoning for specific contexts requires deep understanding of learning science that goes far beyond pattern recognition. As one comprehensive study bluntly states: “AI tools often lack support for high-quality teaching” because “commercial LLMs do not come preloaded with the depth of pedagogical theory needed to design truly effective activities” (Starkey et al., 2025).

Pedagogical judgment and decision-making remain firmly in human hands. Judging appropriateness of AI outputs, making nuanced pedagogical decisions, and balancing competing design constraints all require instructional design expertise that cannot be fully automated (Choi et al., 2024; McNeill, 2024; Wang et al., 2024). The ARCHED framework specifically highlights the critical importance of maintaining “educators as primary decision-makers” while using AI (Wang & Lin, 2025).

Implementation, evaluation, and human-centered tasks require capabilities AI fundamentally lacks. Teacher training needs human mentorship. Providing contextual guidance requires understanding local conditions. Building empathy with learners demands emotional intelligence that AI cannot replicate (Moore et al., 2025; Yang & Stefaniak, 2025).

The Evidence of Mis-Calibrated Trust

The Taylor and Vinauskaitė (2025) research provides smoking-gun evidence of the mis-calibrated trust problem playing out in real time. While 54% of L&D professionals now use AI regularly—a massive increase from 42% in 2023—the practitioner commentary reveals troubling patterns:

“Bad AI has slowed down a process it was hoped to speed up. This is mainly due to the poor quality and unreliability of the output, which often fills in gaps with incorrect information.” (Taylor & Vinauskaitė, 2025)

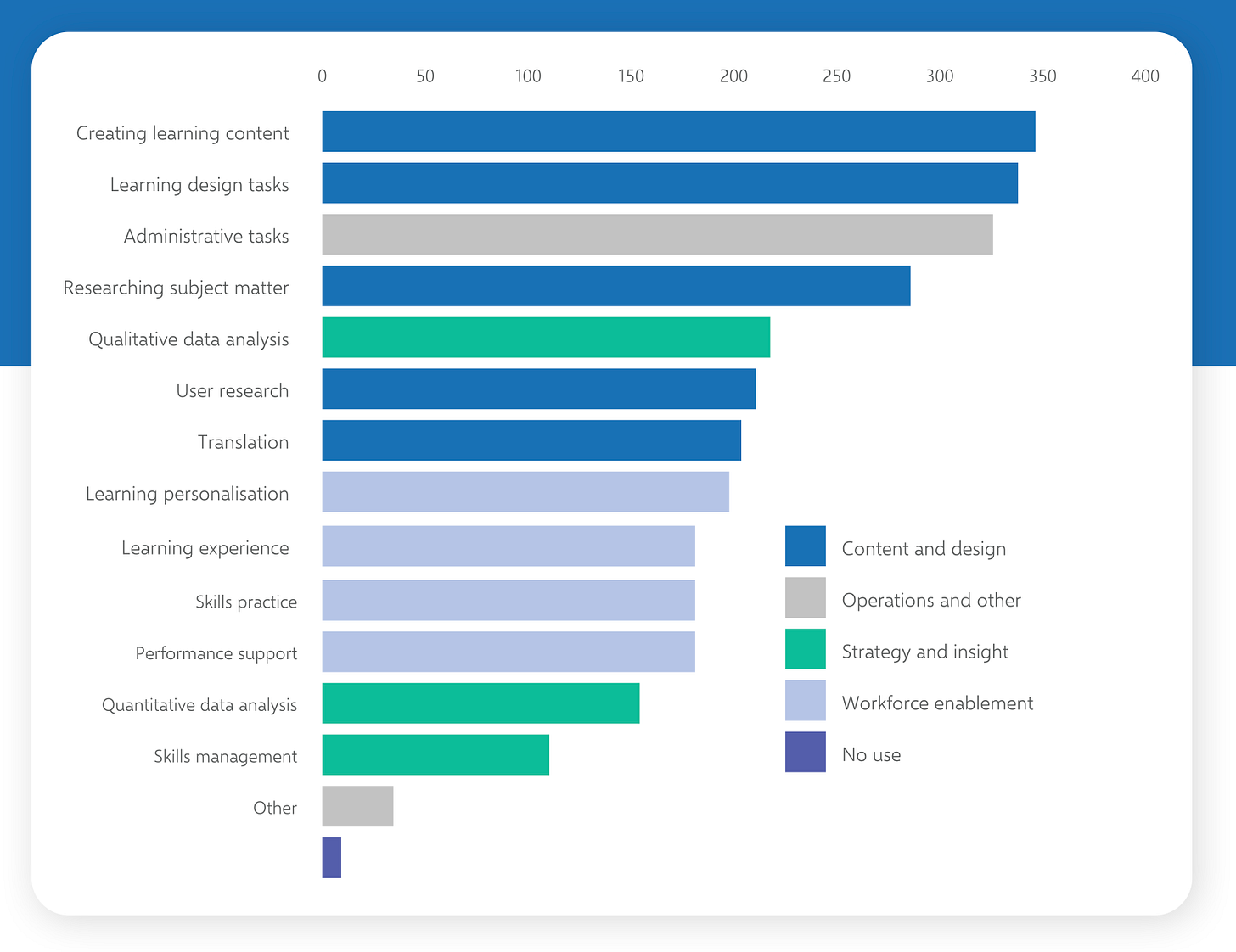

The data shows AI use expanding rapidly beyond content creation into learning design tasks, administrative functions, researching subject matter, and even qualitative data analysis (Taylor & Vinauskaitė, 2025). Leading organisations are pioneering use cases including AI for learning pathway optimisation based on performance data, automated coaching at point of workflow, and synthetic personas for testing learning designs before deployment. But this expansion is happening without the structured understanding of where AI genuinely helps versus where it actively harms outcomes.

Research on AI in instructional design consistently emphasises that successful integration requires “active oversight, critical assessment of AI outputs, and complementarity of AI’s capabilities with designers’ unique insights” (Mollick & Mollick, 2023). Without this awareness, teams experience what researchers describe as “complacency about the AI’s output, errors, and biases” (Mollick & Mollick, 2023), leading to systemic quality degradation.

The over-reliance problem has become acute: 88% of students now use GenAI for assessments (up from 53% last year), showing rapid normalisation alongside concerning patterns where those who “accepted AI suggestions without adaptation” produced “less creative and less contextually appropriate lessons” (HEPI, 2025; Hardman, 2025). This shift toward passive consumption rather than active design thinking represents exactly the mis-calibrated trust the BCG study predicted.

A 2025 study (Yang & Stefaniak, 2025) examining GenAI use among Instructional Designers found that while AI improved efficiency in the design and development phases, designers reported ambivalent attitudes closely linked to concerns about quality, creativity, and over-reliance on AI-generated outputs.

The Quality Crisis Hidden in Plain Sight

Perhaps most concerning is what’s happening to the quality of work produced by Instructional Designers when they use AI. While efficiency metrics show improvement, effectiveness metrics tell a different story:

Reduced consistency of quality

Up to 23% reduction in the quality of some outputs

Growing concerns about generic, homogenised content

Recent research supports these findings and exposes a critical paradox: AI simultaneously promises personalisation at scale while risking creative homogenisation when overused. When used well, AI enables persona-driven design and adaptive learning pathways, with studies showing 29% improvement in concept mastery using persona-driven chatbots (Hardman, 2025). When overused, it produces formulaic, generic content that lacks contextual appropriateness.

A study on AI-generated content found it tends toward being “formulaic” with “shallow emotional resonance” compared to human-created content (Hardman, 2024). Another study examining pre-service teachers using GenAI for instructional design found that those who accepted AI suggestions without adaptation produced “less creative and less contextually appropriate lessons” (Krushinskaia et al., 2024). The convenience of AI assistance, without proper critical evaluation, leads to passive consumption rather than active design thinking.

The BCG study’s most critical finding applies directly here: using AI for tasks outside the frontier doesn’t just fail to help—it actively harms outcomes. The average performance drop of approximately 23% for tasks outside the frontier (Dell’Acqua et al., 2023) mirrors almost exactly the quality reduction Taylor and Vinauskaitė document in learning design practice.

How Much Are We Working Within the Frontier?

The evidence suggests: not nearly enough.

Taylor and Vinauskaitė’s data shows the range of AI use expanding dramatically. In 2023, use was concentrated in content creation and learning design tasks. By September 2025, AI use has spread across a much broader range of tasks:

Learning design and content creation (both over 200 mentions)

Administrative tasks (nearly 200 mentions)

Researching subject matter

Qualitative data analysis

Translation

User research

Learning personalisation

This expansion represents a classic pattern of mis-calibrated trust: practitioners are applying AI to increasingly complex, judgment-heavy tasks without structured methods to compensate for its weaknesses.

Research on Instructional Designers’ GenAI adoption confirms this pattern. A 2025 study found that designers primarily integrate GenAI into the design and development phases—precisely where the frontier gets jagged and human expertise becomes critical (Yang & Stefaniak, 2025). While efficiency improves, designers report ambivalent attitudes stemming from quality concerns and over-reliance on AI outputs.

Another study examining six professional Instructional Designers found they used AI most heavily for tasks requiring creative judgment—generating learning activities, drafting objectives, creating assessment rubrics—but often with insufficient critical evaluation of outputs (Kumar et al., 2024).

The implementation challenge is compounded by a skills gap: many teams are using AI without formal methodology to guide them, with strategy, skills, and resources identified as the top challenges for successful AI implementation (Taylor & Vinauskaitė, 2025).

Pushing Beyond the Frontier: The Path Forward

So how do we push beyond the jagged frontier in Instructional Design and L&D more broadly? The research points to two experimental approaches that some some organisations are implementing:

1. Strategic AI Use: Identifying High-Value Applications

The most successful organisations systematically identify AI opportunities that go beyond speed to measurably improve output quality (Hardman, 2025). This means:

Setting KPIs focused on quality and impact, not just efficiency. Research shows that when organisations focus solely on speed metrics, they miss the quality degradation happening beneath the surface (Dell’Acqua et al., 2023). In my own work, I see that leading organisations are tracking metrics like learning effectiveness, contextual appropriateness and sustained behaviour change rather than just completion times.

Knowing your target and having clear success criteria. High-value AI use cases require Instructional Designers to articulate what “great” looks like using expert sources, define step-by-step processes for achievement, and provide AI with helpful context like team profiles, metrics, and KPIs (Hardman, 2025).

Ensuring business impact through real metrics. Effective AI implementation moves real business metrics—onboarding time, compliance pass rates, manager effectiveness—not just completion times (Hardman, 2025). Case studies show organizations like BCG achieving significant improvements in sales optimisation, Croud documenting 4-5X productivity improvements for repeatable tasks, and MERGE reporting 33% improvement in client work turnaround times with 89% sustained AI usage.

2. Structured AI Methods: Compensating for AI’s Weaknesses

The second critical approach involves using structured methodologies that exploit LLM strengths while systematically compensating for their weaknesses. Where 2023-2024 was the year of prompt libraries and prompting courses which offered low barriers to entry, 2025 was the year that learning professionals realised that more intentional and wide-ranging adoption frameworks were necessary to avoid fragmented adoption and inconsistent results across users.

As AI integration has matured through 2024-2025, an ecosystem of frameworks has started to emerge to guide Instructional Designers in working systematically with AI. Understanding which frameworks L&D teams are adopting—and why—helps illuminate how the field is navigating the jagged frontier.

Here’s the TLDR:

Adoption Model #1: Traditional ID Models Enhanced with AI

These adapt familiar workflows with AI capabilities. ADDIE (AI-Enhanced) integrates AI into the classic Analysis, Design, Development, Implementation, and Evaluation phases, offering incremental adoption within trusted processes—particularly valuable for large teams with established workflows (Chai et al., 2025). However, its linear structure can feel slow for fast-moving AI capabilities, and it lacks specific guidance on AI-related risks like hallucination or model selection.

Similarly, models like SAM (Successive Approximation Model) and 5Di can be accelerated with AI but run a high risk of sacrificing quality for speed.

Adoption Model #2: AI-Native Frameworks

ADGIE (Analysis-Design-Generation-Individualisation-Evaluation) represents a significant evolution, replacing ADDIE’s “Development” phase with “Generation” (AI-generated content) and adding “Individualisation” (AI-driven personalisation). This 2025 framework is gaining traction among ID professionals seeking systematic AI integration while maintaining pedagogical rigour. ADGIE emphasises rapid design cycles with continuous validation throughout, though it’s still emerging in practice and provides evolving guidance on model selection and quality control.

ARCHED (AI-assisted, Responsible, Collaborative, Human-centered, Ethical Design) takes a distinct approach using specialised AI agents for generation and evaluation, with humans making final selections (Wang & Lin, 2025). While this clear human-in-the-loop structure aligns well with educational goals, it requires substantial agent setup and coordination.

Adoption Model #3:Technical & Platform Approaches

Technical & Platform Approaches focus on automation and scalability. Here, L&D teams are playing with agent workflow models which use modular, multi-agent systems to automate document handling, data gathering, design tasks and analytics across the full knowledge work cycle. These approaches are highly scalable but come with significant technical overhead and - given where we are with agentic technology - the need for a intensive human overview. TLDR: automations built into L&D workflows can appear to offer immediate productivity gains but can create bottlenecks, “black box” errors and prove inflexible when AI capabilities rapidly evolve.

Adoption Model #4: FRAME™️: The Risk-Management & Research-Based Approach

FRAME™️, a own method for AI integration in Instructional Design that I have developed, places explicit focus on baking in evidence-based design methods alongside active risk management of AI. It provides structured workflows that align different model types to specific tasks, embed evidence synthesis, implement stepwise risk controls, and use multi-model checks with iterative quality assurance. This approach directly addresses the frontier problem: by systematically compensating for AI weaknesses (hallucination, drift, lack of domain depth), it moves dangerous edge-case tasks inside the frontier.

Evidence from Implementation

The trade-offs between these approaches become clear in practice. Implementation data from organisations piloting FRAME™️ for learning objective generation—a task that typically sits on the frontier’s dangerous edge—demonstrates what systematic risk management achieves:

Significant reduction in time to task completion

Marked increase in output quality, as measured by independent evaluation

Greater consistency across teams

Similar patterns emerge across different approaches. Organisations using ADGIE report improved alignment between AI capabilities and pedagogical outcomes, while ARCHED implementations show enhanced stakeholder confidence through transparent decision-making processes. The critical insight: structured approaches—whether FRAME’s risk focus, ARCHED’s human-centeredness, ADGIE’s AI-native design, or enhanced traditional models—consistently outperform ad hoc AI use.

Research supports this finding. A 2025 study on prompt engineering found that structured prompts with clear pedagogical frameworks significantly improved AI output quality compared to “naive prompting” (Bai et al., 2025). The critical question isn’t whether to use a framework, but which framework’s trade-offs align with your team’s capabilities and risk tolerance.

The Increasingly Critical Role of Human Expertise

Perhaps the most important and least acknowledged implication here is that all emerging approaches fundamentally depend on maintaining and even strengthening human expertise in Instructional Design. In effect, AI requires Instructional Designers to professionalise. Research consistently shows that AI works best when paired with expert human judgment (Dell’Acqua et al., 2023; Moore et al., 2025). Put simply, AI requires Instructional Designers to professionalise.

Perhaps the most important and least acknowledged implication here is that all emerging approaches fundamentally depend on maintaining and even strengthening human expertise in Instructional Design. In effect, AI requires Instructional Designers to professionalise.

A 2025 field experiment with graduate Instructional Design students found that while GenAI assistance improved efficiency, it was most effective when students already had strong foundational knowledge to critically evaluate AI outputs (Moore et al., 2025). Similarly, research on AI tutoring systems emphasises that AI should augment rather than replace human instructional expertise (Chai et al., 2025).

The BCG study introduced two patterns that Instructional Designers should understand:

“Centaurs” divide tasks between themselves and AI, handling strategic decisions while delegating structured work to AI.

“Cyborgs” integrate their work with AI throughout the entire process, using it as a constant collaborator while maintaining critical oversight.

Both patterns require deep expertise to recognise frontier boundaries and validate AI outputs—expertise that becomes more, not less, critical as AI capabilities expand. This expertise gap represents one of the field’s most pressing challenges, with many teams lacking structured professional development to build AI literacy among ID professionals.

Looking Forward: A Field in Flux

We’re now past the Implementation Inflexion. AI is embedded in Instructional Design practice. The question is no longer “Will we use AI?” but “Will we use AI well?”

Interestingly, as AI becomes normalised, we’re seeing what researchers call the “Value Trio Recovery”—three metrics that typically drift downward over time have bounced back in 2025: showing value, consulting more deeply with the business, and providing performance support (Taylor & Vinauskaitė, 2025). After AI dominated 2024 and pushed other priorities down, L&D professionals are recovering focus on business impact and value demonstration. This suggests the field is maturing beyond just AI adoption toward strategic business integration.

The research makes clear what “using AI well” requires:

Understanding the jagged frontier specific to Instructional Design tasks

Implementing structured methods that compensate for AI weaknesses

Focusing on quality and impact metrics, not just efficiency

Maintaining strong human expertise for strategic decisions and critical evaluation

Actively monitoring for quality degradation rather than assuming AI helps uniformly

Developing systematic professional development to address the AI literacy gap

Recent research suggests we’re at a critical juncture. A comprehensive 2025 integrative review of GenAI in Instructional Design concluded that while AI shows promise for supporting ID processes, “the quality and effectiveness of AI integration depends heavily on how well designers understand both AI capabilities and pedagogical principles” (Chai et al., 2025).

The alternative to structured, expertise-driven AI use is already documented: quality degradation, creative homogenisation, and performance losses averaging 23% for tasks outside the frontier. The Taylor and Vinauskaitė research shows this isn’t hypothetical—it’s happening now, in Instructional Design practice worldwide.

As we look toward 2026, an intriguing question emerges: if AI has become so prevalent and is becoming business as usual, does it warrant its own place on trend lists anymore? This signals that the field may be moving from “AI as special topic” to “AI as integrated tool”—similar to how mobile learning evolved from trendy to standard practice.

The jagged frontier in Instructional Design and L&D more broadly is real and it’s here. Navigating it successfully requires not just enthusiasm for AI’s potential, but rigorous attention to where it genuinely helps, where it harms, and how we can systematically push tasks from the wrong side of the frontier to the right side through structured human expertise.

The frontier is jagged, but it’s not fixed. With systematic navigation, we can reshape it to serve better learning rather than undermine it.

Happy innovating!

Phil 👋

PS: Want to navigate the jagged AI frontier with me and a group of people like you? Apply for a place on my bootcamp.

PPS: Want to help us to define the Jagged Frontier in even more detail? Please take ~7 mins to fill in the survey I’m doing with Synthesia (you might even win a place on my bootcamp!).

References

Bai, S., Lo, C. K., & Yang, C. (2025). Enhancing instructional design learning: A comparative study of scaffolding by a 5E instructional model-informed artificial intelligence chatbot and a human teacher. Interactive Learning Environments, 33(3), 2738–2757.

Chai, D. S., Kim, H. S., Kim, K. N., Ha, Y., Shin, S. S. H., & Yoon, S. W. (2025). Generative Artificial Intelligence in Instructional System Design. Human Resource Development Review. https://doi.org/10.1177/15344843251320256

Choi, J., Kim, S., Lee, J., & Moon, J. (2024). Utilizing Generative AI for Instructional Design: Exploring Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats. TechTrends, 68(1), 23–44.

Dell’Acqua, F., McFowland, E., Mollick, E. R., Lifshitz-Assaf, H., Kellogg, K., Rajendran, S., Krayer, L., Candelon, F., & Lakhani, K. R. (2023). Navigating the Jagged Technological Frontier: Field Experimental Evidence of the Effects of AI on Knowledge Worker Productivity and Quality. Harvard Business School Working Paper No. 24-013.

Hardman, P. (2024). Exploring AI-Driven Social Media Content Creation Benefits, Barriers, And Good Practices: Experts’ Interviews. Journal of Internet Business, 45, 4542625.

Hardman, P. (2025). Beyond the Hype: What 18 Recent Research Papers Say About AI in Instructional Design. Dr Philippa Hardman Newsletter, June 23.

Hardman, P. (2025). FRAME: The AI Playbook for L&D. [PDF document]

Harmon, S. W., & Odom, M. L. (2023). Combining Human Creativity and AI-Based Tools in the Instructional Design of MOOCs: Benefits and Limitations. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies.

HEPI (2025). Student Generative AI Survey 2025. Higher Education Policy Institute.

Krushinskaia, K., Nazaretsky, T., Alexandron, G., & Alexandrov, M. (2024). Effects of generative artificial intelligence on instructional design outcomes and the mediating role of pre-service teachers’ prior knowledge of different types of instructional design tasks. In A. M. Olney et al. (Eds.), Artificial Intelligence in Education: Posters and Late Breaking Results (pp. 395–400). Springer.

Kumar, V., Boulton, H., & Baraniuk, R. G. (2024). AI-Augmented Instructional Design: Affordances and Constraints from Subject Matter Expert Perspectives. Educational Technology Research and Development, 72(4), 892-910.

Law, A. K. K., So, J., Lui, C. T., Choi, Y. F., Cheung, K. H., Hung, K. K. C., & Graham, C. A. (2025). AI versus human-generated multiple-choice questions for medical education: a cohort study in a high-stakes examination. BMC Medical Education, 25:208. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-025-06796-6

Luo, T., Lee, A. R., & Stefaniak, J. E. (2025). Beyond Brainstorming: Investigating the Impact of Generative AI on Instructional Designers’ Creative Diversity. Computers & Education: Artificial Intelligence, 6, 100234.

McNeill, L. (2024). Automation or Innovation? A Generative AI and Instructional Design Snapshot. The IAFOR International Conference on Education – Hawaii 2024 Official Conference Proceedings, 187–194.

Mollick, E. R., & Mollick, L. (2023). Assigning AI: Seven Approaches for Students, with Prompts. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.10052.

Moore, S., Eckstein, L., Kwon, C., & Stamper, J. (2025). Integrating Generative AI into Instructional Design Practice: Effects on Graduate Student Learning and Self-Efficacy. In K. Tammets et al. (Eds.), Two Decades of TEL: From Lessons Learnt to Challenges Ahead (pp. 342-358). Springer.

Ruiz-Rojas, L. I., Acosta-Vargas, P., & Salvador-Ullauri, L. (2023). Empowering Education with Generative Artificial Intelligence Tools: Approach with an Instructional Design Matrix. Sustainability, 15(15), 11524.

Starkey, L., Shonfeld, M., Prestridge, S., & Cervera, M. G. (2025). Enabling Multi-Agent Systems as Learning Designers: Applying Learning Sciences to AI Instructional Design. arXiv preprint arXiv:2508.16659.

Taylor, D. H., & Vinauskaitė, E. (2025). AI in L&D: The Race for Impact. The L&D Survey Series. Donald H Taylor and Associates.

Wang, Y., & Lin, X. (2025). ARCHED: A Human-Centered Framework for Transparent, Responsible, and Collaborative AI-Assisted Instructional Design. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.08931.

Wang, Y., Chen, L., & Lin, X. (2024). Teaching Plan Generation and Evaluation With GPT-4: Unleashing the Potential of LLM in Instructional Design. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies.

Winder, G., Bass, S., Schiele, D., & Buchner, J. (2024). Using Large Language Models for Content Creation Impacts Online Learning Evaluation Outcomes. International Journal on E-Learning, 23(3), 305–318.

Yang, Y., & Stefaniak, J. E. (2025). Instructional Designers’ Integration of Generative Artificial Intelligence into Their Professional Practice. Education Sciences, 15(9), 1133.

Articles like this show why Dr Phil is the absolute rockstar in this field!